Game History

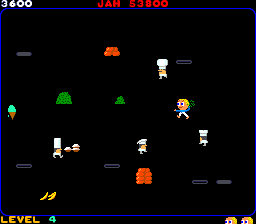

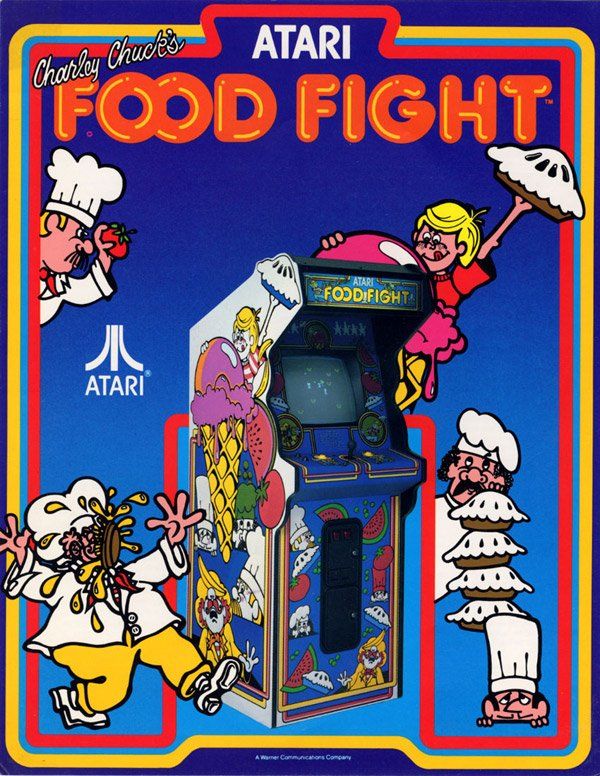

Charley Chuck’s Food Fight

Publisher/Manufacturer: AtariDeveloper: General Computer CorporationRelease Year: 1983

By Mike Stulir • Vice President, The American Classic Arcade Museum

Charley Chuck’s Food Fight has always been a popular game at The American Classic Arcade Museum. It has unique gameplay and a “cute” style that appeals to all ages, both men & women.

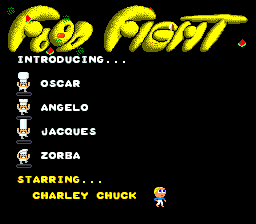

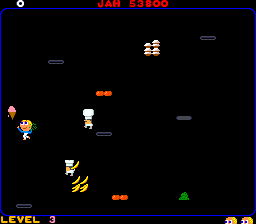

You control Charley Chuck. The object of the game is for you to move Charley across the screen and eat the ice cream cone before it melts. In your way are a group of angry chefs (Angelo, Zorba, Oscar and Jacques) who are out to stop you. Littered around the playfield are piles of watermelon, bananas, pies, and other foods. Charley can pick up food and hurl it at the chefs, but they may do the same to you. If you are hit by food, step in a pothole, or touched by a chef, you lose a life.

Food Fight was unique in its era due to a number of features. It was one of the earliest games to use a Motorola 68000 series processor, which gave the game incredible processing power and opened up a new range of features and graphics never seen before. It also used an analog joystick that gave the player an almost unlimited amount of control for movement.

The game was eventually ported to the Atari 7800 console, and the Atari XL/XE computers. It also appeared in Atari’s “Flashback” console released in 2004.

Food Fight was developed by General Computer Corporation (GCC) in Cambridge, MA. GCC was responsible for a number of arcade games, and countless ports of arcade games to arcade consoles. They are also the company that designed the 7800 console for Atari.

Recently, ACAM had an opportunity to talk to Jonathan Hurd, the creator of Food Fight, to get the real story of the history of the game:

ACAM:

What is your educational background and what led to your hiring at GCC?

JH:

I received my bachelor’s degree in Computer Science from MIT, and after graduation in 1979 I joined Strategic Planning Associates, a strategy consulting firm, as a software developer. We wrote financial analysis software used by strategy consultants and our Fortune 500 clients. In 1980, I was put in charge of hiring summer interns from MIT, and one of the interns I hired was Kevin Curran (one of the founders of GCC). In late 1981 I heard that Kevin and others had started a video game company, and when there was a major change underway at SPA, I gave Kevin a call and asked if he were hiring software engineers. He said yes, and I enthusiastically accepted his offer—I had always loved arcade games—and became the 9th employee at GCC.

My first day on the job was a few days before Christmas in 1981. I went into Kevin’s office and said, “So, you know my background, what should I do to get started here?” Kevin said, “Come up with an idea for a video game, build it, and we’ll all get rich.” It was just what I wanted to hear—more than anything else I wanted to create a new arcade game!

I walked out of Kevin’s office, and in the lab Mike Horowitz and the team were working hard to finish the final changes to Ms. Pac-Man. I asked Mike if I could do anything to help, and he said, “See if you can fix her lips—they’re looking a little funny.” So I spent an hour or so on our rudimentary character development system trying different combinations of red and yellow pixels for her lips and lipstick. (Sometimes I say to people, “I helped put the touches on Ms. Pac-Man’s lips.”)

ACAM:

What was the inspiration for the game?

JH:

The first few days on the job I spent a lot of time playing the games we had in our office—for example, Tempest. I also went to arcades to play games, watch other people play games, and talk to other players. I wanted to come up with something different—something that was less violent, possibly funny, and that would appeal to both male and female players. Most games had a “Fire” button, and so I thought, “What else could a button do?” I’m a baseball fan, so I thought “Throw.” But throw what? I thought “Food!” Once I had the idea for “Food Fight” I immediately realized it was a great name and idea, so I was inspired to create the game quickly before someone else did. I wrote a game proposal on January 4, 1982, and ran it by Doug Macrae, Kevin, and others for feedback. In terms of game play, the original game proposal is amazingly similar to what we ultimately created, although the characters and controls evolved as we refined the game.

ACAM:

Who were the other members of the development team and what were their roles?

JH:

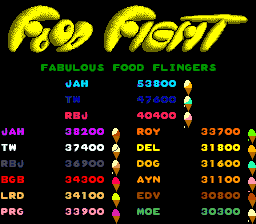

In many ways, everyone at GCC contributed to the game’s development. Kevin and Doug believed that people should have offices—a quiet place where they could do focused work—but all the game prototypes were out in the open, in a central “lab” environment where we all spent most of our time. So we would all play the games under development and give each other ideas. It was a very collaborative environment. Just to give one example: when I first put up the high score table on Food Fight, its title was something generic like “Food Fight High Scorers”. Mike Feinstein said, “Why don’t you call it something more interesting, like ‘Fabulous Food Flingers’?” A few minutes later I changed the title, and that’s what stuck. People generated lots and lots of ideas—I still have pages of original notes I kept when people suggested ideas. The trick was figuring out how to take all the ideas and decide which ones made sense given the overall game play and tone we were trying to create for the game.

Game Play Action!

View more

The initials of the people who were most heavily involved in creating Food Fight are in the high score table:

TW:

Tom Westberg designed the game’s hardware. Kevin and Doug’s vision was that we would create a re-usable hardware platform for our arcade games, which would reduce development time and in theory also reduce production costs, bugs, etc., so that we could focus most of our attention on the games themselves. Tom’s design was rock solid—after all these years, many of the original Food Fight games still run perfectly.

RBJ:

Roland Janbergs contributed many ideas and wrote a lot of the code, especially in the initial months when we were rushing to get prototypes ready for demos to Atari executives that periodically came to visit GCC. I’ve still got a lot of the old “To Do” lists where Roland, Bruce Burns, and I would split up tasks (e.g., making sure that holes and food piles didn’t overlap, making the chefs behave differently, having different characteristics for the foods).

BGB:

Bruce Burns worked with me on the original prototype in January 1982, and then assisted part-time while he was a student at MIT. Bruce and I wrote the original Food Fight prototype on Pac-Man hardware, which was based on a Z80 processor. So the initial Food Fight code was in Z80 assembly language, and then Roland, Bruce, and I converted it to Tom’s 68000-based hardware.

LRD:

Larry Dennison worked with Tom on the hardware design.

PRG:

Patty Goodson was our resident musician. She wrote some of the tunes for Food Fight, most notably the Instant Replay music.

ROY:

Roy Groth designed the sound hardware and developed many of the sounds, such as the food “splatting” sound.

DEL:

Dan Ludwig wired up the original version of Tom Westberg’s hardware design, and later worked on layout for the printed circuit board. He also helped me get the prototype game assembled into a generic cabinet so that we could take it to a local arcade—Fun & Games on Route 9 in Framingham, MA—where I’d hang out for hours watching people play prototype versions of Food Fight to get ideas for refining the game.

DOG:

Darrell Myers was one of four visual artists we hired at GCC to do our graphics and animations. He created the doughy-looking Food Fight title which is spelled out during the introductory sequence, and improved a lot of the graphics.

AYN:

Art Ng was one of GCC’s hardware engineers and designed the game’s analog circuitry.

EDV, MOE:

Ed Vallee and Maurice Vincent assisted Dan Ludwig with the printed circuit board layout.

By the way, my initials come up as JAH, but if you enter 7 backspaces followed by JAH when you get a high score, my monogram (rather than my initials) will appear. It’s the only “Easter egg” in the game.

ACAM:

Food Fight is one of the earliest examples of the Motorola 68000 processor in an arcade environment. How did the introduction of that processor change arcade games? Was there a fundamental shift in requirements for development? Did that processor allow arcade games to do things never before attempted?

JH:

The most striking benefit of the 68000 was the increase in processing power. Tom’s hardware design allowed for 32 moving characters (we called them “stamps”; often they’re called “sprites”). At times during the higher-level rounds of Food Fight, all 32 are in use—for Charley Chuck, for the chefs, and for many pieces of food flying around, each with its own set of calculations for direction, speed, and distance. (In fact, if a new piece of food is needed, the stamp for the food closest to being “finished” is used.) Meanwhile, the code constantly checks to see whether Chuck or any of the chefs are hit by a piece of food. So the amount of calculation and the on-screen motion was quite intensive (by early ‘80s standards)!

The 68000 platform also allowed us to write a lot of the game in C rather than assembly language. The C compiler was a bit buggy and inefficient, so I wrote and rewrote many of the time and space-sensitive portions of the code in assembler to make them run faster. But having most of the game written in C allowed for great flexibility, so when someone suggested an idea it was easy to try it, see what it looked like, and make refinements. That was the biggest advantage of writing the game in a high-level language.

Over the course of several days, Jobs & Woz worked around the clock and came up with a circuit design for Breakout. Woz did the majority of the work with Jobs handing the breadboard wiring. Atari opted not to use the Woz/Jobs prototype. Woz’s prototype design, while brilliant, lacked the circuitry necessary for coin-drop detection and on-screen scoring. To make matters worse, Atari had concerns about replicating the design in the manufacturing process. Despite not using the Wozniak design, Atari still paid Jobs the $700 designer bonus and a $5,000 bonus for reduction of integrated circuits. Jobs did not disclose the additional bonus to Wozniak and only paid Wozniak half of the $700 design bonus. Wozniak did not discover this until many years later.

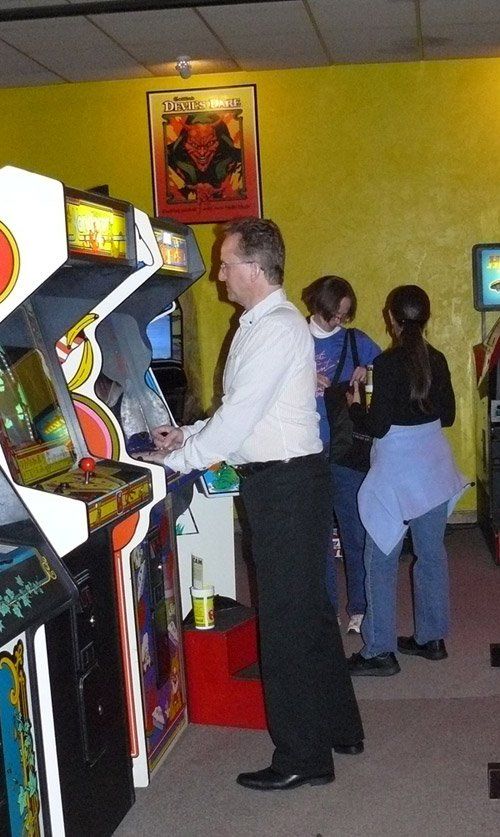

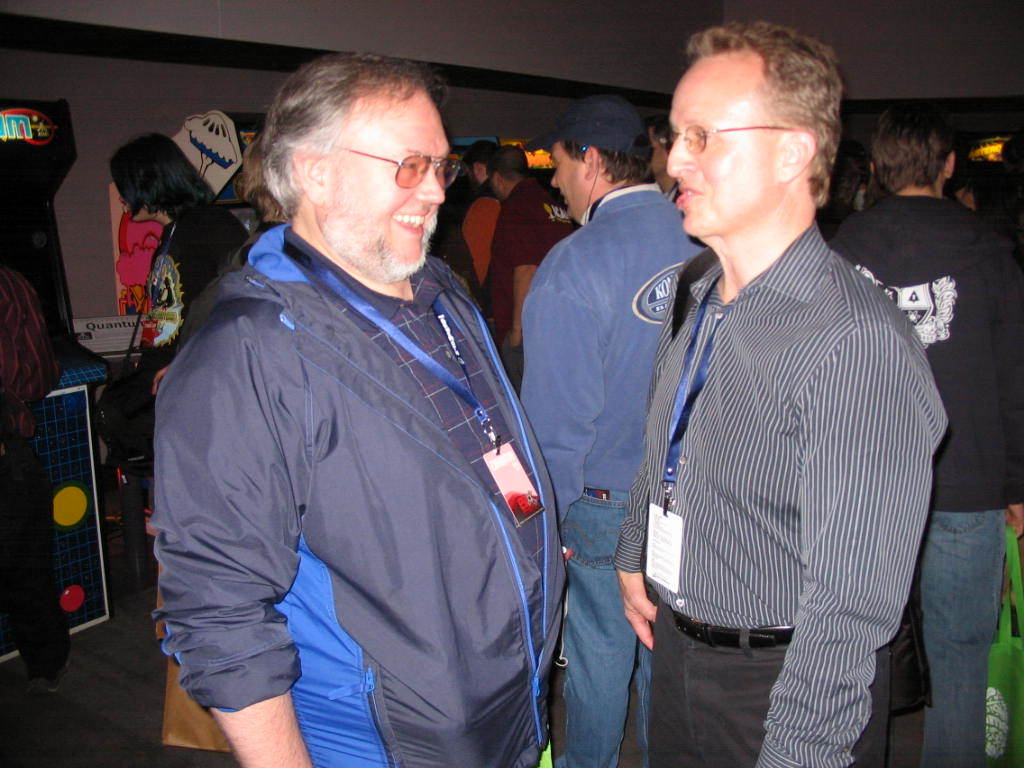

ACAM Board member Mike Stulir visits with Food Fight creator Jonathan Hurd at PAX-East 2012

ACAM:

Can you talk a little bit about the development equipment used to design the game?

JH:

We used a Tektronix 8560 as our development system. It was a multi-user Unix-based computer which had a file system, editor, C compiler, and 68000 assembler. Each of the prototype games under development had a probe attached in place of the processor, and the probe was attached to a specialized computer—a Tektronix 8540—which was running a 68000 emulator. This allowed us to run the prototype game as if it had a 68000 chip in place, but actually the 8540 was emulating a 68000 and was running the prototype.

When we had a version of the code ready to test, we would transfer it from the 8560 where it had been assembled, and load it into the memory of the corresponding Tektronix 8540. From there, we could use the emulator to run the game, which allowed us to set breakpoints (stop the processor) where we could examine contents of the 68000’s registers or memory locations.

I still have the pricing for a 4-station 8560/8540 development environment…a whopping $144,000 (and that was in 1982 dollars!). Computing and memory was a lot more expensive in those days—for example, the 64K (64,000 bytes) “extra memory option” for each 8540 was $3,450!

ACAM:

Can you discuss the “instant replay” feature? You mentioned to me some time ago that programming that feature into the game had some unique challenges.

JH:

Food Fight’s hardware had 8K bytes of RAM (Random Access Memory), in addition to the 64K of program ROM (Read Only Memory). In RAM we needed to store positions, directions, and durations for all the moving objects, but beyond that the RAM requirements were minimal. At one point I realized that we had about half the RAM left over, and that by storing the state of the joystick and the throw button in RAM, we could recreate a level of the game after it had occurred. (Everything else about the game was deterministic—even though things happened in a random or semi-random fashion, such as the speed and duration of the watermelon, or the chef’s behavior—those random things were based on a random number generator which used a seed. So by storing the starting random number seed it was easy to recreate a level.)

I can’t remember where the idea originally came from, but at one point I put in an instant replay feature which would happen randomly after someone finished a level. It was a unique feature, but the problem was that if the level was not exciting, then watching an instant replay was boring. So then I changed it so that the instant replay would happen only if the level was “exciting”—the player had to have at least one close shave with flying food and with a chef. Then we realized it would be great to have music accompanying the instant replay, and Patty Goodson composed original music. The tricky thing here was that an instant replay could last anywhere between 8 and 30 seconds, so Patty wrote 8 different versions of the music and then in software I played the appropriate version a little faster or a little slower so that the tune started exactly when the level started, and ended exactly when Charley Chuck ate the cone.

By the way, there are lots of things that could be better about Food Fight, but the only serious bug that I know of has to do with the instant replay feature. If you eat the cone at the last possible moment, AND you’ve had a round that’s exciting enough to trigger an instant replay, then the game resets itself completely! Very bad bug…wish I had caught it before the game went into production. And very sorry if you’ve been in the middle of a great game and had this happen to you.

ACAM:

We have heard some rumors that the original design for the game used a trackball as the controller. Is that true?

JH:

The control was initially the biggest challenge, eventually the best feature, but ultimately the biggest problem with Food Fight. Initially, since we used Pac-Man hardware to get a quick prototype up and running, we used the Pac-Man joystick as the control, but it didn’t have enough positions. So believe it or not, we switched to a knob so that movement/throwing could happen in any direction, combined with a MOVE button and a THROW button. But then we found that we were always moving, so we changed to MOVE button to a STOP button! Imagine, a game with a STOP button! It was reasonably effective, but completely non-intuitive. When we first demoed the game to Atari executives on March 4, 1982, it had those bizarre controls but despite that was reasonably fun to play. We considered a lot of different options, including a track ball and two joysticks like Robotron, but didn’t actually implement those.

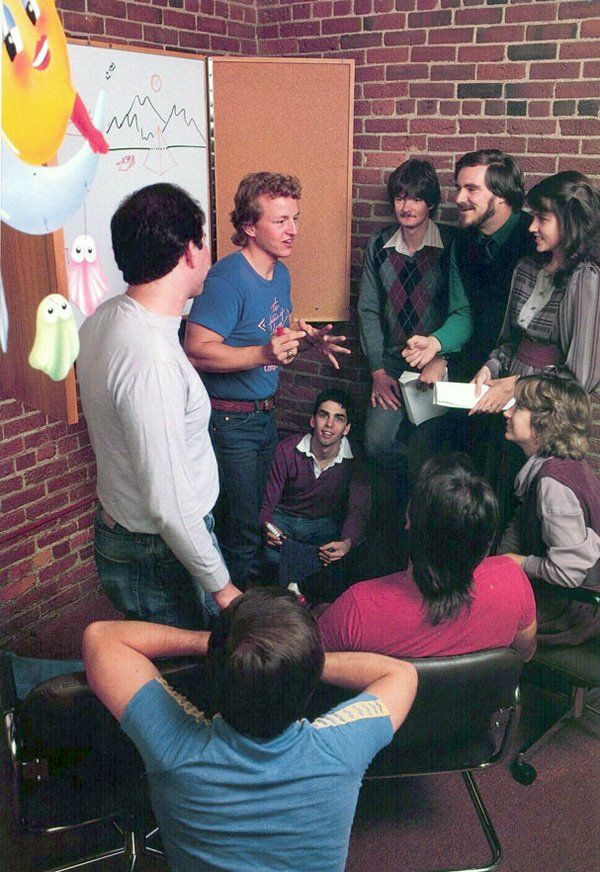

Jonathan Hurd (r) chats with Jr. Pac-Man creator Tim Hoskins at PAX-East 2010

Then around that same time we realized that we could use an analog joystick, similar to the one on Red Baron, combined with a THROW button. That joystick had two potentiometers, one for the horizontal (X) position and the other for vertical (Y). Each potentiometer was hooked up to an analog to digital converter, so that it gave us one byte for X and one for Y. We created a grid of possible joystick positions, where the X and Y gave an angle, so you could point and throw in one of 72 different directions (we split 360 degrees into 72 possible angles with 5 degrees between each angle). If you stayed nearer the middle of the grid, you didn’t move, but you could throw in any direction. If you moved the control to the edge of the grid, you would move in that direction. This created a lot of flexibility, because you could stay on a pile of food (like the infinite watermelon pile) and keep throwing in any direction, or you could throw while moving.

The problem was that the Red Baron joystick design was not sturdy enough to handle the forces put on it by Food Fight

players. Even though Atari tried making design changes, they happened too late in the process. The early games shipped performed really well in arcades, but the joystick broke frequently, and many arcade owners gave up on it.

ACAM:

Were there any features or ideas that did not make their way into the final product?

JH:

It would not be an exaggeration to say that for every idea that was incorporated into Food Fight there were 10 that were left out. Here are some examples:

- For one of the arcade tests, I bought (in a Bradlees store, I think) one of those plastic bananas that some people must use in a bowl of decorative fake fruit. I filled it with epoxy, and inverted the handle of the joystick into it. When dry, we had a banana joystick! People at the arcade loved it—it grabbed their attention immediately. Unfortunately, the epoxy-filled banana added a lot of weight to the top of the joystick, and the first person that gave it a good shove broke the joystick mechanism. Great idea, poor execution…

- The original game proposal had the idea of a crowd which would be visible at the top of the game, which would cheer, groan, etc., depending on what happened. The crowd then spawned the idea of having the game set in a Roman Coliseum, complete with Roman-named characters wearing togas, Roman numerals for the levels, etc. When we decided on using chefs for the enemies, the Roman thing didn’t really make sense. We also realized that we needed as much screen real estate as possible to support the game play, so we dropped the idea of the crowd, which would have been a unique visual feature but wouldn’t have made the game any more fun to play. Game play was always the most important consideration in our design.

- After Chuck eats the cone, the leftover food pieces are worth 100 points each—the food goes flying from the piles to the player score for emphasis. One alternate idea was to have a maid come on the screen to clean up the piles that were remaining.

ACAM:

What other games did you work on during your time at GCC?

JH:

After we shipped the final Food Fight ROMs to Atari on March 21, 1983, I was put in charge of running our arcade games group. We had about a dozen people working on arcade games, and a much larger team working on home games and game systems—ultimately we did more than 50 home games for Atari. The arcade game Jr. Pacman, which was led by my friend Tim Hoskins, was completed during this time. We had several other arcade games under development in 1983 through early 1984, but the video game industry was going through a crash and none of those games were brought to market. As a side project in late 1983 to early 1984 I worked on a prototype for a voice recognition toy called Baby Backtalk. I was on a team we formed to explore software development for the Apple Macintosh in 1984, which is when I left GCC.

ACAM:

With so many classic arcade game developers coming back to design games for smartphones, tablets and home console games, have you ever given any thought of developing titles for those platforms?

JH:

I still love games, but professionally I’ve changed careers a couple of times and for the past 20 years I’ve been a strategy consultant focused on technology, media, and communications. I’m still involved with games as well as other forms of entertainment and media, but from a strategy perspective rather than a creative one. Perhaps when I retire I’ll get back to writing software…

ACAM:

Whenever we see you at ACAM or at PAX-East, you always play a round or two of Food Fight. What are some of your other favorite games of the era?

JH:

I always admired Robotron and thought it was the most exciting game ever developed. In fact, the high levels (100+) of Food Fight were intended to be like Robotron in terms of their speed and intensity. For whatever reason though, I was never as good at Robotron as Tom Westberg and some of our other guys—I never mastered the dual joystick controls.

We had a cockpit Pole Position at GCC which I’d play when I needed a break, and I got pretty good at that—I could usually set the high score at arcades. Galaga was also one of my favorites.